Precocious teenage Cartesians, of a nerdy philosophical bent, often suppose they can ask:

‘It’s possible, isn’t it, that what I experience as blue, you experience as red. I could never know, because I can’t get into your head and see colours the way you do, but it’s possible, isn’t it, that if I did, the world would look completely different to me than to you?’

It’s a question that makes no sense, at least to precocious teenage Cartesians who have gone on to study philosophy. We can’t get at the idea at all using the language and concepts that we learn in the world, pointing at things together and agreeing on the application of words. Even if you’re in some mysterious sense ‘experiencing’ blue as my red, we’ll point at the same things and use the words ‘red’ and ‘blue’ in complete agreement.

It’s only in abnormal cases such as colour-blindness that we can agree that things look different, and that’s because there are ways to establish that someone sees colours unusually – normal sighted and colour-blind people disagree on the application of colour words, systematically.

Words and thought won’t stretch to the idea that ‘privately’ our experiences might be different. You might as well suggest that a square might ‘privately’ look like a circle to me, What can we usefully do with such an idea? I’ll never be able to say, ‘Oh, he’s one of those people who sees blue as red, or circles as triangles.’ How could I know, and what would we do with this ‘knowledge’?

Not that private experience of all kinds is unreachable. Private experience is reachable if we can agree on it publicly. For example, we can make sense of the idea that we can see a single image ‘as’ one thing and then another, as long as we can point and explain. ‘Private experience’ makes no sense when we can’t point at anything or explain in any way.

I can see this cartoon image either as a rabbit or a duck.

‘Look, this is it’s bill,’ you might say, or ‘Look, they could be ears instead.’

And I’ll know when you get the point. Though I’ll never be able to ‘catch’ you seeing it one way or the other. That part is private.

I was thinking these thoughts at the recently reopened Picasso Museum in Paris on Saturday, whilst looking at some of Picasso’s early Cubist works. Through Cubism Picasso and others were trying to convey how an object is ‘really’ perceived and understood by a spectator rather than simply to ‘capture’ how it looks front-on from a particular perspective. It’s obvious, of course, that we don’t perceive objects as a camera does, all at once, with a quick snap of the shutter. Our eyes travel, we shift our point of view, and our mind constructs an understanding of an object as it might be seen from multiple dimensions. Construction going wrong is what happens when you try out LSD, I suppose (though I never have!).

Here’s how Picasso captures the reality of a man with a guitar.

Construction is perceptual, emotional, and intellectual, all at the same time. Good painters add attitude, anger, lust or love to the line and colour mix.

So, Cubism supposedly shows us how we really perceive an object, perspectives all mixed up, a consciousness of two eyes, face-on and in profile simultaneously. Perhaps the fragmented, multi-dimensional prose of Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake aims to capture the ‘real’ world in the same kind of way, its prose assaulting the reader from multiple angles and levels of consciousness, all at once, as the world does. We get paintings that are hard to look at, some might say, and prose that’s impossible to read. Perhaps they both leave us with too little to do ourselves, or, when they become, impenetrable, too much.

But for those still of a philosophical bent there’s a logical problem with Cubism. The painter supposedly shows us how we really perceive an object, through the medium of a painting. But a painting is an object too, which we also perceive and know in complex ways (perhaps we imagine the blank hessian at the back even while we’re gazing in rapt attention at the front). So, it’s a complicated experience. A painter conveys the experience of an object through the experience of a painting. His, and our, experience isn’t of a flat and neutral object hanging on a wall. It’s more complicated. Ultimately another’s experience is elusive, and perhaps Cubism, the more it strives, takes things too far. It can’t ever really succeed.

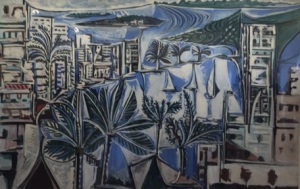

But, there’s truth in the idea, too, and success. Look at Picasso’s evocation of the real Cannes, the whole Cannes.

David Hockney does something similar, conveying everything, all at once, about a regular car journey he made from home to studio, combining knowledge and image into a single complete and personal experience, and finding a way to share it.

We’re condemned, as individuals, to see things from a single point of view, and must use whatever means we find to share our personal perspective. Paint, music, words, and the rest, they work up to a point.