Learning how to develop and manage Apps has been a difficult and essential experience for our development team at systems@work. ‘Mobile’ is the buzzword these days, even if last week it was ‘Cloud’.

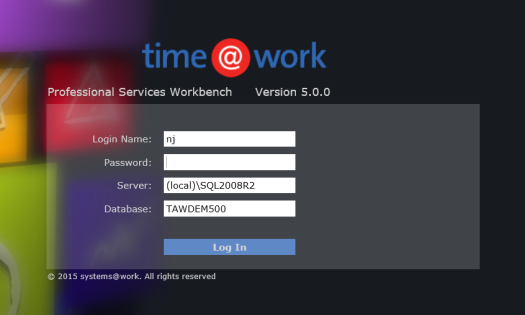

We recognised three or more years ago that we needed to develop an App for our largely browser-based ERP software – time@work for Professional Services Management, expense@work for Expense Management, and forms@work for forms workflow management. In some ways it’s not easy for traditional ERP developers and consultants such as we are to learn the new tricks of the App world, but if you’re in the business of packaged ERP software you’ve got to keep up with technology and be near the leading edge, if not quite at the edge itself. Just as the browser revolution demanded that we think in a different way both technically and in terms of user experience, so the App imposes new demands. Apps must be even easier to use, indeed almost a joy, manipulable with a single finger or thumb. But making the complex seem easy is always a challenge with complex business applications.

The tradition with Apps is always keep it simple, or, rather keep it looking simple and easy to use. Specialist terminology must be avoided, and functions must be intuitive and easy to use. The space you have to work with is small, but nothing must look cramped. Obviously there’s no point in crying RTFM when users complain that they don’t know what to do next. If your Granny can’t use it, you’ve probably failed the keep it simple rule.

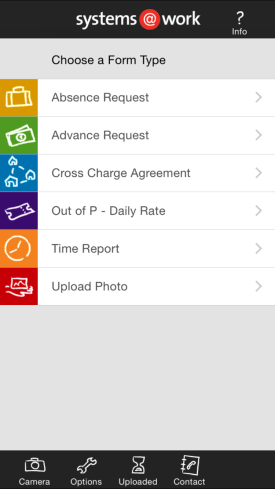

But ERP systems are complex, and our systems@work software is highly configurable. It’s all about forms – forms for expenses, forms for absence requests, forms for recording time on projects, forms for stock movements, forms for this and that. You can configure a form to do any number of things, offering different fields with different lists of items, calculations with different rules, and so on. You can also attach photos and record voice memos and use forms in any number of different languages. You can also set up any number of form types and control who sees which ones.

All the lists, labels, definitions and rules that form types need are held by our system in a central database. So we have to make everything work with a single App, an App that can read and download these rules and interpret them on your mobile device. Moreover we need to make this download work swiftly. You can’t keep Granny waiting.

Apps must also work whether you’re online or offline. Actually, that’s not a necessity, but given that the rules that govern forms must be downloaded to the simple database that sits inside your mobile, then why not? Some of our users have been clamouring for years for a way to enter their expenses offline whilst flying, for subsequent upload in the Arrivals Hall. So it was part of our plans to produce an App that could be used offline as well as online.

We set ourselves these objectives:

- Our App must be easy to use

- Our App must look good

- Our App must work with any configuration of our software

- Our App must work offline and online

- Our App must be fast in terms of upload of data and synchronisation

iPhone technology is very different from the Microsoft technology we were used to, and we had a difficult choice, either to find an iOS expert and teach him or her how our system works, or retrain one of our programmers on iOS technology. We chose the latter but had recourse to App expertise when we needed it. Even so, it took nearly 18 months to develop the first version of our App, together with all the server-side web services we need to serve it.

Take up is gradual but accelerating, and yesterday we released Version 2.0, taking account of immediate feedback from our users. We’ve improved usability, extended the use of the App to include form authorisation, and improved graphics. In the coming weeks we’ll release an Android version, and in the coming months a Windows Mobile version.

There’s also one more challenge that ERP software authors face – how to manage the release of App versions. The problem is that ‘delivery’ is uncontrolled. Release an App to the App Store and everyone gets it almost immediately. It’s got to work first time for every Client who’s already using it irrespective of their configuration, and without a chance to run in test mode. This also implies that each new version must be compatible with prior versions of the core software. We’re still thinking about how to do that in the best possible way.