If you’re bicycling through southern Hunganry and the adjoining (formerly Hungarian) province of Vojvodina in northern Serbia, you can’t but be aware of the terrible displacements and atrocities that have been committed in the region by one ethnic, religious or cultural group against another over the last several centuries, and even quite recently, nearby.

One such atrocity, the Nazi murder of the Jewish population of the region, stands out. So, still, do the beautiful synagogues of Szeged and Subotica, both of which I saw earlier this week. They are a stark reminder of the sheer size of the Jewish communities in these two cities, communities which, as I understand it, are virtually non-existent, or very small, today.

The synagogue in Szeged (1907) is the fourth largest in the world, and the second largest in Hungary, after the Dohany Street Synagogue in Budapest. It is in good condition and is used as a concert hall as well as for worship.

The synagogue in Subotica (1902), inspired by the great Hungarian architect Odon Lechner, was built for a community that numbered around 3,000 at the time. It’s another great example of Hungarian art nouveau.

Both great buildings are evidence and poignant reminders of the Jewish life and culture that must have been part of everyone’s everyday life in these and other cities in Central and Eastern Europe and the Balkans until the 1940s.

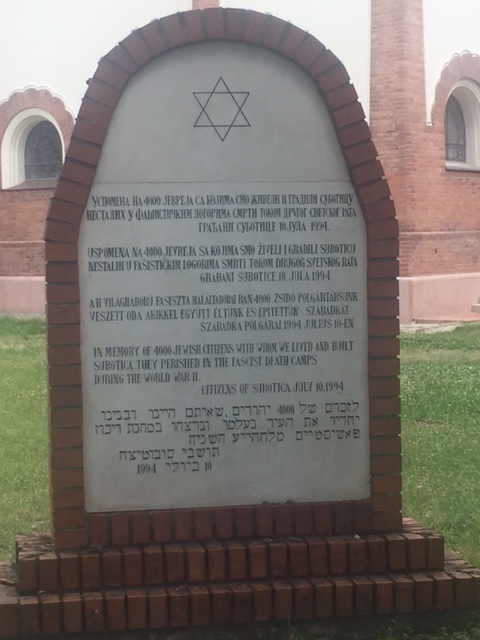

But I write about this mainly because I am intrigued by the language of the memorial tablet placed outside the Subotica Synagogue:

The Jews, it says, ‘perished in fascist death camps.’ So, it seems to imply, that had nothing to do with the local populations, or local hatreds. It all happened in a faraway place.

The description places the blame on ‘fascism’, as if anti-Semitism was, and is, principally a matter of political ideology, rather than something with darker, less intellectual origins (an irrational hatred that lay at the heart of Christian European culture for centuries)- something that can be ‘educated’ away, and blamed on specific political leaders rather than on the population at large. Of course, I may be maligning the people of Subotica. I don’t know if they were exemplary in their protection of the Jewish community (as Serbia was, in general) or not. Even if so, the description is misleading. The murder of the Jews was not a ‘fascist’ crime. It was not a German crime. It was a Nazi crime, inspired by the leaders of the Nazi party and supported by millions of others, in Germany and elsewhere, who shared their hatred.

The inscription dates from 1994, a time perhaps when Communist ideology was still lingering in the country (Yugoslavia still?) and it was convenient to wipe the slate clean and claim that in the absence of ‘fascism’ the danger no longer existed.

But I remember a train journey I made from Belgrade to Budapest in the summer of 1987, when both Hungary and Yugoslavia were still nominally communist. I talked for an hour or so with a pleasant middle-class lady who was eager to practise her excellent English. For some reason we got onto the events of the Second World War and I asked a few questions about Jewish survivors, and about the scale of the transportation and murder of the region’s Jews.

‘I know it was awful,’ she said. ‘And it’s awful that the Jewish communities were almost entirely destroyed, but you know we never really liked them.’

So much for the eradication of the irrational by political re-education! Anti-Semitism was not specifically a fascist phenomenon.