…I’ll go mad. I was in Buenos Aires last week, and I couldn’t get away from them.

Just imagine, instead, that you’re in London and wherever you go, in every café and restaurant, on every street corner, there are Pearly Kings and Queens doing their cheerful Cockney thing, bawling out ‘Down at the Old Bull and Bush…’. You’d want to die.

Or that you’re in Vienna and the waltzing just goes on and on.

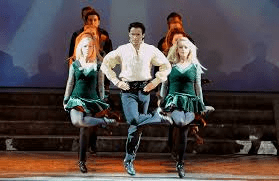

Or in Dublin, and Michael Flatley’s Riverdance hordes are bearing down on you with those awful foot-banging Irish dances.

Or in Wales and there’s a male voice choir singing ‘Bread of Heaven’ from every mountain top.

All of these tiresome celebrations of national culture (and we can all think of dozens more) should be abolished or very severely restricted (only between 11 am and 4 pm, for example, on the last Thursday of the month, and never in front of children). These national clichés hold their nations back. They come to define a country and blind us to its other virtues.

It’s time for these anachronistic curiosities to be abandoned. Buenos Aires must outlaw the tango, and move on less gracefully. It’s not as if it’s the only thing they’ve got to celebrate. They’ve got beef, Evita, financial crises, and new world wines. Vienna has horses, stollen and Mozart. Ireland has writers and Guinness. Wales has a lovely accent. Every country’s Tourist Board should carry out an annual, unsentimental cull, ridding us of whatever sits at the top of its list of nation-defining delights. They have delighted us long enough.

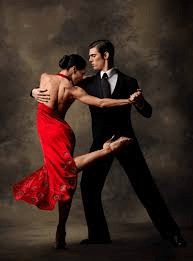

I write this after an excruciating evening of tangos in a nightclub at an upmarket hotel in Buenos Aires. It was dinner followed by a show in a room that resembled a tart’s boudoir (I’ve never been in a tart’s boudoir, but I’ve seen them in films). Red plush velvet, prim pin-cushion chairs that were agony after ten minutes, and darkness. There was hardly sufficient light to eat by.

It was a very long haul indeed from 8.30 pm until the show began at 10.15 pm (though the food was good) and I promise that, even so, I approached the show with an open mind. But after five minutes of the artificially heightened drama of five couples tangoing furiously in 1920s fashions, I was more than ready to turn my face to the wall. Tango, it seems to me, is just sulking on legs. It may take two to tango, but it’s usually only the lady who’s doing the sulking. If I were her partner I wouldn’t put up with it for more than a minute. For some reason, though, he always does, and in the end she always bends to his will. You see, it’s sexist too.

The skill, judging by the occasional applause, lies in the intricate twirling of the legs, which can be astonishingly rapid and complicated, even if utterly unnecessary. The truth is that an interest in ladies’ legs is a prerequisite if you’re to enjoy a show such as this. I see now that it must have been precisely the twirling of ladies’ legs, even if by pouting and sulking East Midlands Latin American wannabes, that attracted my father to Come Dancing, the BBC’s TV dance show of the 1970s. I was fonder of Match of the Day, perhaps for a similar reason. But each to his own.

On top of everything else, the violinist was out of tune.

So, that was the last tango for me.