I was amused by an article I read a few days ago (Bridge is Not a Sport) about a High Court ruling on the definition of sport. I’m not sure that it will finally settle those pointless arguments between drunk men in pubs, but I’m hopeful. I’ve noticed that people even come to blows over definitions, perhaps especially if they’re concerned with sport.

‘Darts definitely isn’t a sport,’ one drunk might scornfully say to another.

‘It involves precise physical activity and astonishing mental acuity,’ another might say.

‘But no sport can involve the consumption of beer.’

‘If darts isn’t a sport, then neither is synchronised swimming. No sport can involve the wearing of makeup.’

‘What about Ice dancing?’

And so on.

Last week the High Court ruled definitively that Bridge isn’t a sport, endorsing the judgement of Sport England, who denied funding to Bridge, claiming that all sports must involve physical activity.

But, actually, what makes an activity a sport? For one reason or another (none of them good ones) we seem to hanker after precise and all-encompassing definitions. But it’s not an easy task.

A sport must involve physical activity.

Yes, but nearly everything does, so that’s nowhere near a precise enough definition.

A sport must involve physical activity that’s a deliberately acquired and precise skill.

That conveniently excludes Bridge, since the physical activity of laying down playing cards isn’t a deliberately acquired skill but a naturally acquired one common to all human beings over a certain age. This definition enables us still to include Darts, Football, and so on.

But what about running?. That’s a naturally occurring skill.

We need to refine our definition. Perhaps we can do something purpose.

A sport must involve physical activity that’s pursued mainly for the pleasure or self-improvement of the individual and or spectators.

But, that would include playing the violin in an orchestra.

Should we introduce the idea of competition? That might rule out most violin playing, but not all of it. And some sports, such as long-distance bicycling and running, can be solitary.

Entertainment? No, some sports aren’t spectator sports.

Rule-governed? No, there aren’t any rules governing running.

Requiring extreme physical exertion? No, think of bowls, or darts, or shooting.

Resulting in physical improvement or fitness? No, too narrow.

Some will counter by saying, ‘No, bowls isn’t a sport, it’s a pastime.’ But such distinctions are arbitrary and you won’t obtain a consensus on the matter, especially if the inebriated are involved.

If you think of all the Olympic Sports you won’t find a common defining characteristic that couldn’t be found in activities that aren’t sports. In order to arrive at a definition, we think, we must find a set of properties that are necessary and sufficient for an activity to be called a sport, and we can’t.

It’s a waste of time. But it’s faintly disturbing. We think that if we can’t devise a definition then the word won’t have a secure meaning.

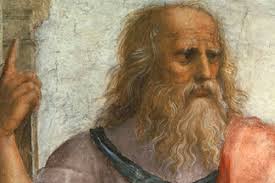

Philosophers have struggled with this issue for years. Plato was convinced that behind every concept there’s an ‘ideal form’ that captures the essence (in effect, the defining qualities) of things. And science, with its explanatory programme, has supported this by finding essences in things. An ‘alcoholic beverage’ must contain a certain chemical (though we might, for convenience ignore ‘trace quantities’). And ‘red’ means a certain range of wavelengths. And so on.

But you don’t have to stray far from basic things amenable to science to run into trouble with definitions. What’s a table? What’s a party? What’s a sport?

Plato started with the definition of Justice at the beginning of The Republic, and he didn’t entirely settle the matter.

The definition of words is context and convention dependent and sensitive to purpose. Look at the High Court ruling carefully and you’ll see that it’s a ruling in relation to Sport England’s founding principles and purposes. It’s a sensible ruling that refers to a particular organisation that was created for a particular purpose. It needn’t be a final definition for all contexts and purposes.

Even so, Sport England ducks the definition issue on its website.

Sport England is committed to helping people and communities across the country create sporting habits for life.

This means investing in organisations and projects that will get more people playing sport and creating opportunities for people to excel at their chosen sport.

The question of what’s a sport isn’t tackled at all.

In fact it’s only when Sport England faced a legal challenge from the Bridge-playing community that they reached for any kind of definition, arguing narrowly, that Bridge doesn’t involve physical activity. They’d have to make a different argument if they were challenged by an orchestra.

Definition isn’t absolute. It depends on context and purpose.

When it comes to sport, what would we make of Gloucester’s remark in King Lear? What precise all-encompassing definition of sport could capture this meaning?

![karlin_divadlo_povodne[1]](https://adambager.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/karlin_divadlo_povodne1.jpg?w=300&h=200)